World War 1

NEIL LEYBOURNE SMITH'S

HISTORY OF 3 SQUADRON, AFC, RAAF

(First published as a Video-History © 1989)

If you would prefer to go directly to a particular section of the history, please click on one of these pictures:

Early World War 2 (up to Alamein)

Late World War 2 (to war's end)

![]()

My father, Lieutenant James Leybourne ("Lee") Smith, was a pilot with 3 Squadron, A.F.C, during World War I. He also re-enlisted for the duration of World War II from 1939 and 1945, to serve as a Wing Commander at RAAF Headquarters in Melbourne, Victoria. During his six month operational duty in 1918, he flew 113 patrols over France and was awarded the Distinguished Flying Cross. Ground fire shattered his ankle and forced him to make a crash-landing on 10 August 1918 in his RE8 (C2275), which he’d christened "Pyancus" and which had a representation of this mythical creation painted on its fuselage.

He spent the remaining few months of war in hospital and went through the rest of his life with a gammy leg until his death in 1973 at the age of 80.

In the early 1940s in particular, when I was just a lad, whenever he'd read or heard about 3 Squadron's outstanding work with the Desert Air Force, he'd often recall and recount incidents to me from the Squadron's history. In recent years, it occurred to me that other children and grandchildren of 3 Squadron members may like to know more about how and where their fathers or grandfathers, uncles or cousins devoted the prime years of their young lives, during the two world wars in particular, and the dangers they lived with during the years they served.

So, with the invaluable assistance of several dedicated 3 Squadron World War II veterans and by reference to selected books written about both wars and about the Squadron in particular, I’ve created this chronological history especially for the families of 3 Squadron members...

Many of the visual supports are old and sometimes tattered and faded black and white photos loaned to me by ex-Squadron members from their personal souvenirs... others are official war photos.

But, in all, I hope they will collectively recount for you the history of Australia's most distinguished Air Force Squadron.

Neil Smith

3

Squadron veterans inspect a replica of the Red Baron's

Fokker Triplane at Williamtown.

(Left:

Former

Commanding Officer Bob

Gibbes and wife Jean. Foreground: Former Padre Bob

Davies.)

![]()

On

the 70th "Birthday" of No.3 Squadron RAAF (Friday, l9th September

1986) the airmen and airwomen of 3 Squadron proudly received a new Squadron

Standard at their Base in Williamtown, NSW, Australia.

On

the 70th "Birthday" of No.3 Squadron RAAF (Friday, l9th September

1986) the airmen and airwomen of 3 Squadron proudly received a new Squadron

Standard at their Base in Williamtown, NSW, Australia.

This event reinforced the quite extraordinary camaraderie that has continually surrounded 3 Squadron for the best part of a century; the existence of a particularly strong emotional bond that connects everyone who has ever been associated with its magnificent and unique history.

Many of the Squadron's battle honours had never been recorded on the old Standard, so it was retired to the Chapel at Point Cook in accordance with tradition; leaving the new Colours to display for all to see, at the Squadron's present Headquarters, an embroidered precis of the most important events in the Squadron's life. Each location has a story you'll be proud to share - stories true to the Squadron's motto: "OPERTA APERTA", which means: "SECRETS REVEALED."

Today, 3 Squadron’s personnel are custodians of much more than the Squadron's heritage. They're in control of the most sophisticated aircraft in Australia ... entrusted to the Squadron as a favoured protector of the nation.

Their service life stands in strong contrast to that of their predecessors, simply because the technical expertise now involved in flying and supporting the Squadron's latest F-35 (Lightning II) fighters is completely different from the day-to-day operational life of years past. As well, in those days gone by, the Squadron was predominantly at war and it used aircraft, equipment and methods now considered to be quite primitive.

Those dramatic contrasts over so many years need to be recorded for posterity, as should the fact that the Squadron is unique in Australian history: being the Squadron that has served the nation for the greatest number of years as a unit of both the A.F.C. and the subsequently-formed R.A.A.F.

Firstly we look at those early pioneering Australian Flying Corps years…

PART 1 : WW I (began on 4 August 1914 and ended on 11 November 1918)

Port Melbourne, Vic. 1916-10-25. Personnel of the newly formed "No.2 Squadron" Australian Flying Corps

[later re-numbered to become 3AFC] wait on the wharf to embark on the troop transport ship SS Ulysses (A38)

for service overseas. [AWM P00394.021]Our story begins with 18 officers and 230 airmen who had been assembled at the Australian Imperial Forces camp next to the Central Flying School at Point Cook in Victoria, Australia. It was the 19th of September 1916 and already the War in Europe had been raging for over two years. The men were a mixture; some were Army men who'd completed courses at either Central Flying School or Wireless School. Many were civilians with previous flying experience. But they'd all volunteered to fight overseas with this newly-formed Squadron, which at this embryonic stage had been designated to be 2 Squadron, Australian Flying Corps - simply because it was the second Squadron to be formed in Australia.

On the 25th of October 1916, after only minimal basic training, these young men - most in their early twenties - sailed on the S.S. Ulysses from Port Melbourne bound for England to complete their training.

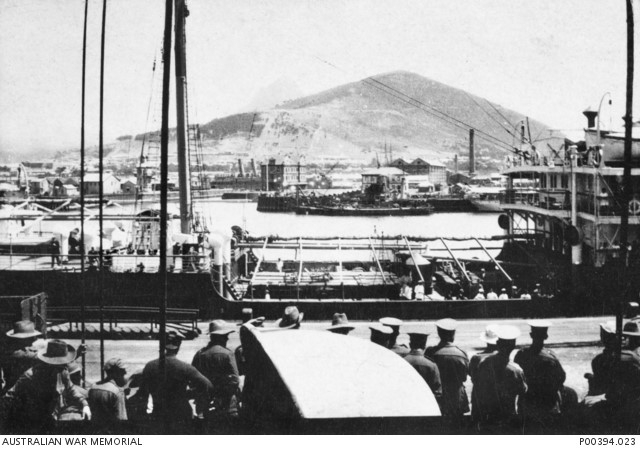

CAPE TOWN, SOUTH AFRICA. 1916. THE

TOWN AND MOUNTAIN IN THE BACKGROUND, SEEN FROM

THE TROOP TRANSPORT SHIP SS ULYSSES CARRYING MEMBERS

OF THE AUSTRALIAN FLYING

CORPS NO. 2 SQUADRON TO SERVICE IN EUROPE.

[AWM P00394.023]

After travelling around the Cape and through Durban and Freetown, the Ulysses' convoy was delayed because of enemy submarines. It finally took nine weeks for the Squadron to reach Devonport, England. Christmas 1916 was spent on board, but New Year's Day, 1917 saw the Squadron settling in at an aerodrome in South Carlton, near Lincoln where they were to spend the next eight months learning how to fly aircraft, operate as a reconnaissance squadron and practice the principles of aerial combat.

Beautiful South CarltonAs soon as they arrived they were told that the Squadron was to be called "No.69 Australian Squadron, Royal Flying Corps", but three months later, this was changed by War Office Memorandum, dated 31st March 1917, to "No.69 Squadron, Australian Flying Corps" and it first fought in France under that designation until, on the 18th of January 1918, the Squadron officially became 3 Squadron, Australian Flying Corps.

[The previous designation of "2 Squadron" had meanwhile been taken by another AFC squadron formed in the Middle East.]At South Carlton, and at the Training Schools at Reading and Oxford where some of the Squadron's non-commissioned ranks were transferred to train as Commissioned pilots, rotary engine "pusher"-type biplanes were used for flying training.

Grahame-White Boxkites were one of the earlier types used. These extraordinary combinations of wires, struts and fabric were powered by 50-horsepower Gnome engines which gave a top speed of 50 miles per hour.

Other training aircraft used were the Maurice Farman Longhorn with its obtrusive front elevator, and its successor, (being blessed with short landing skids) the Shorthorn. Most student pilots complained ... saying that not only were these ugly-looking aircraft named after cows, they flew like them as well! They were made with wooden struts with wire bracing and fabric covering and the pupil sat behind the instructor in the nacelle mounted on the lower wing. The biplane was powered by a 70-horsepower Renault pusher engine and had a top speed of 59 miles per hour. The obvious difference between the Longhorn and the Shorthorn was, of course, the shape and length of the protruding outrigger landing skids although later model Shorthorns were fitted with Renault engines generating an extra 10 horsepower, to give them a top speed of 70 miles per hour. The Shorthorn was called the "Rumpety" by student pilots because of the rumbling noise it made while travelling over the ground. But all student pilots were still required to complete at least six 30-minute dual- instruction flights in these types of trainers before they were allowed to fly solo.

ENGLAND C 1917. PORT

SIDE VIEW OF MAURICE FARMAN SHORTHORN B 2034

USED FOR INITIAL TRAINING OF PILOTS FOR THE AUSTRALIAN FLYING CORPS

(AFC). [AWM

P00743.015]

After that they had to fly a minimum of five hours solo in more difficult-to-handle Avro 504s, aircraft which almost all Australian, British and Canadian World War 1 pilots flew, at some time or other, during their training.

Avro 504 in the UK.

[AWM C00803]

This was an aeroplane with a long and respectable pedigree. The particular model of the two-seater biplane which many 3 Squadron personnel flew, was the 504K ... the 12th model developed by the A. V. Roe Aircraft Company since 1907. Different types of engines were fitted, but the fastest was the 130-horsepower Clerget engine which gave the aeroplane a top speed of 95 miles per hour, and a higher than usual service ceiling of over 16,000 feet.

In those days, a pilot was sometimes awarded his wings after only 12 hours solo flying but usually 20 hours were required, plus the successful completion of some special tests such as making a few landings at unfamiliar aerodromes while on long distance cross-country flights; flying to high altitudes before gliding from 6,000 feet with the engine switched off to touch down inside a marked 50 yard circle; a couple of night landings with only flares for a landing guide; bomb dropping; aerial photography; signalling; machine gunnery; artillery observation; formation flying and - of course - air combat practice.

At 3 Squadron’s base in South Carlton and at some of the Training Schools, instruction was also given in flying other types of aircraft including the well-known, but not always loved, BE2E. Originally intended for reconnaissance with the observer sitting in the front cockpit and the pilot in the back, it could only fly at about 80 miles per hour at 6,000 feet making it too slow and vulnerable for combat... at least that was the joint opinions of No. 1 Squadron who were using them in Egypt and several R.F.C. Squadrons using them in France. Nevertheless, a few BE2Es were used by 3 Squadron for both training and practice at their own airfield but luckily, the Squadron wasn't allocated these underpowered, under-armed and unmanoeuvrable aircraft for their coming Front Line operations.

Instead, during June and July 1917, they were issued with the Royal Aircraft Factory's latest and greatest creation: the "RE8". Nick-named "Harry Tate" after a popular musical artist of the time, they became the Squadron's main operational aircraft until the War was over.

RE8

on the Western Front with 3 Squadron.

The letters "RE" stood for "Reconnaissance Experimental" and the "8" represented the eighth of the model designs. Only a few models in the "RE" series were produced from the time the model RE1 was manufactured in limited numbers in 1913 until this new RE8 was designed.

It was the first British two-seater production aircraft to place the observer in the rear cockpit so he could get a clear shot at any pursuing enemy while the pilot in front flew the aeroplane and shot at any enemy in the flight path with the fixed (port-side) Vickers machine gun, synchronised to avoid hitting the rotating propeller blades.

Many of the pilots in the 18 RFC and AFC Squadrons who used the 4,077 RE8s manufactured during the war were wary of them at first, because they seemed prone to go into spins and the petrol tank’s location behind the engine often caused fire in a crash. But 3 Squadron quickly learnt to rig and balance them correctly, as stability was essential for flying photographic missions.

The Royal Aircraft Factory's 150-horsepower "4a" engine reliably propelled the RE8 at a maximum speed of 102 miles per hour with an endurance range of 4¼ hours, allowing a longer flying range than any other reconnaissance aeroplane being used on either side during the War. While it would climb at 65 miles per hour, it was considered difficult to manoeuvre. But it was sturdy with a solid frame.

Air mechanics of the 3rd Squadron, Australian Flying Corps,

overhauling an R.E.8 Aircraft belonging to B Flight at the

Squadron's airfield.

Left to right: Corporal (Cpl) Bromfield (standing on ground);

unidentified (back to camera); Cpl Bryant;

Air Mechanic Second Class (2AM) J. G. Buchanan; 2AM F. W. Morgan. [25 October 1918. AWM

E03676]

But compared with other British reconnaissance aircraft, its 13,500 feet ceiling height was 2nd only to a Bristol Fighter, the F2B, known as the "Brisfit". (Excellent for reconnaissance, the F2B could fly at 123 miles per hour at 4,000 feet if fitted with the usual 275 horse power Rolls Royce engine. It climbed fast to 20,000 feet and performed so well that it was used more as a Fighter and a Bomber than a reconnaissance aircraft. A flight of these very popular aircraft was eventually attached to 3 Squadron, but not until the last few months of the war.)

On the 17th of August, 1917, an advance party consisting of 73 mechanics and 57 vehicles were called upon to carry out orders from the 23rd Wing, Royal Flying Corps, to move the Squadron to France. They arrived in Rouen and quickly began preparing for the arrival of the Squadron's 18 RE8s which were to fly from South Carlton four days later, on the 21st. Unfortunately only 17 aircraft arrived, as one went down on the way, killing its pilot and passenger-mechanic.

By the 4th of September, 1917, the Squadron had travelled north-east from Rouen for almost 100 miles, to Savy, about 8 miles NW of Arras. They were to remain at Savy for the next two months. Thus, 3 Squadron (although, at that time, they were still called 69 Squadron, Australian Flying Corps) became part of 1st Wing, 1st Brigade, R.F.C. and so became the very first Australian Squadron to go into combat on the Western Front.

Lieutenant (Lt) Stanley George Brearley, pilot, and Lt Robert Harold

Taylor, observer, of No. 69 Squadron (Australian), Royal Flying

Corps (RFC),

starting out from the hangar at Savy. They

are seated in an RAF RE-8 aircraft; a

two-seater biplane with forward-firing and

rear-firing

machine guns, mostly used in artillery observation and bombing

roles. Note the numerals on the top

fuselage decking and white circle Squadron insignia.

[AWM E01178, Savy, 22 October 1917. This magnesium-flash

photograph was probably taken by the famous Australian

photographer Frank Hurley.]

The Squadron's first taste of operations was to act as a support force to Nos.5 and 16 Squadrons R.F.C. who were also part of 1st Wing. Their support duties involved the Squadron in 12 inconclusive air combats while they were carrying out 142 artillery patrols and pin-pointing 11 enemy batteries for destruction by artillery. In those early days, the Squadron used rather primitive but nevertheless effective air observation techniques to direct army artillery fire onto targets. Each operation would start with RE8s patrolling designated areas of enemy territory.

Often they'd be subjected to heavy ground-fire or be under attack from enemy aircraft while they carried out these patrols, but the RE8 observers would still mark their maps with the exact locations of any enemy gun emplacements they'd sight and, as soon as their RE8s landed, they'd give these maps to the Squadron Recording Officer who would immediately send them, by dispatch rider, to the Army Artillery Staff. Certain targets would be selected for destruction according to the needs of the Army's constantly changing battle plans.

RE8s would then be sent back over these targets to photograph them using one or both of the cameras fixed by the ground crew to the aircraft. One of these cameras was vertically-mounted under the observer's seat, while the other was fitted under the wing and connected to the cockpit with a Bowden wire control that was used to remotely expose and change the photographic plates. This wing camera was used to take oblique photos of ground contours and installations generally, while the vertical camera was used to take overhead photos.

Back at the aerodrome, the plate-negatives would be immediately developed by the Squadron's Photographic Section, which consisted of as many as 14 photographic personnel. They would sometimes work all night, at busy times, to print many hundreds of photos. An image in the form of a clock-dial would be superimposed over some of these developed prints, locating the target dead-centre on the clock-dial with the 12 o'clock position pointing true north. Circles at radial distances representing 10, 25, 50, 100, 200, 300, 400 and 500 yards from the target were lettered Y, Z, A, B, C, D, E and F respectively. Copies of these "clock code" photographs were then dispatched to nearby Army Artillery Batteries as well as to the RE8 crew assigned to carry out the Artillery ranging.

After take off, the RE8 would wait for the Battery to lay out a giant white linoleum-formed letter "L" on the ground to signify the Battery was ready to commence firing. The RE8 would then cruise at about 85 miles per hour towards the target area and, using the RE8's Standard Sterling Transmitter with its 120ft-long trailing aerial, they'd key (in Morse Code) the letter "G" to let the Battery know they could let "go" with their salvo.

On the ground, near each Battery location, a 3 Squadron Wireless Operator would receive the RE8's signal on his crystal detector receiver, using a "cat's whisker" tuner, headphones and an aerial pole about 30 feet high. Incidentally, the "cat’s whisker" had to be continually re-tuned to the point on the crystal which gave the best signal reception because, as the shoot progressed, the receiver would be constantly jolted by the concussion from the Battery's guns and the enemy’s counter-bombardment.

Nevertheless, the RE8s signals, relayed to the Battery, would start each salvo and the RE8's job was to note where each salvo fell in relation to the clock-face on the photograph and to then signal the Battery with the clock-code-letter designating the distance the salvo fell short of the target. Of course, the Battery would keep correcting its aim, always trying to hit the target, while the RE8 would continue to fly in large circles between the Battery and the target to report changing circumstances.

On 8th November 1917, the Squadron successfully completed its first bombing mission. The six RE8s of "A" Flight were armed with 40 pound phosphorus bombs for laying a protective smoke screen against enemy interference while the six RE8s in "B" Flight, loaded with 20 pound Cooper Bombs, and "C" Flight's six with 112 pounders, were bombing enemy positions in the village of Neuvireuil.

Four days later, on November 12th, the Squadron again moved north, this time to Bailleul near the Belgian border (SW of Ypres) where they were to remain until a few days before the end of March, 1918.

The RFC had two Squadrons based nearby ... 53 which operated their RE8s in conjunction with 9th Corps and 19 Squadron who, with their Spads, were a Scout Squadron. By then, 3 Squadron's strength consisted of 45 Officers and 278 Airmen including almost 100 wireless operators.

Everybody quickly settled down to their work as the "Corps Squadron" for the 1st Anzac Corps and, by 6th December, in spite of bad weather, Captain W. H. Anderson's observer, Lieutenant J. R. Bell shot down the Squadron's first enemy aircraft, a D.F.W. two-seater.

An extraordinary incident happened on the 17th December 1917, when an RE8 piloted by Lieutenant James Sandy with his observer, Sergeant Henry Hughes, was ranging artillery fire for the 8-inch Howitzers of the 151st Siege Battery. 35 minutes after they'd started, they were attacked by six Albatros D.Va Scouts. Lieutenant Sandy fought them off and, before long, he'd shot one down close to Armentieres.

About then, two other 3 Squadron RE8s who happened to be nearby, came to Sandy's assistance. Within a few minutes, the remaining enemy aircraft broke off the fight and headed for their own lines. (In itself, this wasn't unusual because German pilots generally held great respect for the RE8 with the pilot's propeller-synchronised Vickers machine gun and the observer's Lewis gun to defend the rear.)

The Albatros D.Va forced down by

Sandy and Hughes, preserved today in the AWM, Canberra.

After the enemy aircraft had left, both of the other RE8s clearly saw that Sandy's RE8 ... number A3816, with the unmistakable letter "B" on the fuselage ... was flying straight and steady, so they waved a farewell and flew off to resume their own assignments. However, Sandy's wireless messages directing the Artillery Battery had ceased transmission. By nightfall, A3816 had not returned to the aerodrome.

Fellow WW1-pilot Lee

Smith's watercolour of the "Ghost RE8". [Neil Smith

Collection]

On the following night, a telegram from Number 12 Stationery Hospital at St. Pol told of finding the bodies of the two airmen in their grounded RE8 in a neighbouring field. A postmortem of the bodies and an examination of the RE8 showed that both pilot and observer had been killed in aerial combat and that the RE8 had flown itself around in wide left-hand circles until its petrol ran out.

What had happened was that a single enemy armour-piercing bullet had passed through the observer's left lung and thence into the base of the pilot's skull. The RE8 came down 50 miles south-west of the battle scene out of skies that hadn't seen any other aerial combat that day. It had crash-landed without further injuring the bodies of the airmen and with the throttle still wide open. The aircraft itself was not badly damaged in spite of its uncontrolled 50 mile flight and this, in itself, was a classic example of the stability and flying qualities of the RE8.

An unexploded German

100kg aerial bomb (Harold

Edwards Collection)

Twice in that December, the aerodrome at Bailleul was attacked by German Gotha bombers who dropped 250-pound bombs from about 8,500 feet but they failed to damage the aerodrome.

A Sopwith Camel from the RFC's 65 Squadron brought down one of the Gothas and that was about all the excitement that the Squadron were to experience during the months that followed, because the irregular weather at times turned into gales and snowstorms and stopped all air activity in the area. Heavy bombardment from enemy long-range guns on the Bailleul area made life even harder. It was during one of these barrages when the weather was at its worst, that an instruction was received saying the Squadron was no longer to be called 69 Squadron, but 3 Squadron, Australian Flying Corps. The date was the 18th of January, 1918; thus 3 Squadron was officially christened.

February through to March involved the Squadron in many photographic missions around the Armentieres area where fighting was intense. Some flights were assigned to drop propaganda leaflets over enemy rest-camps well behind the front line. Their purpose was to unsettle the enemy by letting them know that good food and warm billets awaited them if they choose to surrender. However these missions were discontinued after it became known throughout the Corps that pilots brought down in enemy territory while dropping leaflets were treated brutally by the enemy.

Crashed RE8 (Harold

Edwards Collection)

By the 22nd of March, the enemy shelling had risen to such a pitch that the Squadron could no longer operate out of Bailleul.

That afternoon, they moved to Abeele and the very next morning a direct hit by a 14-inch shell on the vacated officers' quarters killed one and wounded two of the clean-up squad still working there. Had this happened 24 hours earlier, perhaps a dozen or more pilots or observers could have been killed or at least badly injured in their quarters.

It turned out that their stay at Abeele was to be a short but busy 15 days and for the ground crew; quite exciting because it was there they had a rare opportunity to see one of their RE8 crews in a dogfight with a German DFW almost over the aerodrome. The RE8 out-flew and out-shot the DFW and eventually brought it down only a few miles from where they stood watching.

3 Squadron left the Armentieres-Ypres Front with the honour of being the top Squadron in the 2nd Wing, Royal Flying Corps, having located and reported the greatest number of enemy artillery positions in the Wing and assisted in the greatest number of Artillery Ranging missions as well.

They moved south on the 6th of April, 1918 to a hot-spot in the War ... the Somme Front. Already, eight other Squadrons were fighting there when 3 Squadron took up their position as part of 15th Wing, Royal Air Force, in an open airfield near Poulainville.

They quickly started work carrying out reconnaissance missions for the Australian Corps to locate enemy batteries and, using the "zone call" system, direct our own artillery fire onto the enemy positions.

The area was well defended by the Germans on the ground and in the air. The famed "Richthofen's Circus", the crack German Jagdgeschwader 1 ... itself made up of Jastas 4, 6, 10 and 11, was based near Cappy, and only about 20 flying miles east of the Squadron's aerodrome.

Death of the Red Baron

One of the most memorable yet contentious events of the entire War in the Air occurred on the 21st of April, 1918 and 3 Squadron were right in the thick of it! The incident began about 10 o'clock on that hazy Sunday morning when two RE8s took off from 3 Squadron's aerodrome near Poulainville on a routine mission to photograph the Front Line - only 12 miles away. As they flew East towards their designated target area, they and several other British aircraft flying nearby were seen by enemy spotters who immediately alerted the German aerodrome at Cappy.

Rittmeister Baron Manfred von Richthofen, Germany’s 25-year-old Ace of Aces, who had first arrived at the Western Front as a cavalryman 32 months beforehand, was flying his red Fokker Drl triplane, numbered 425/17, which had already helped to earn him the name of the "Red Falcon". (The modern moniker of "Red Baron" was coined in the 1930s.)

Within minutes of his take-off, six other differently-coloured triplanes joined him to form the "Richthofen Circus" as both friend and foe called these multi-coloured "Jagdgeschwaders" (or fighter wings) that flew the skies in the early months of 1918.

Before long, more triplanes and some Albatros aircraft from Jasta 5 joined the circus ... turning it into a pretty strong formation cruising west at about 90 miles per hour towards the two RE8s from 3 Squadron, who were by then flying at 6,000 feet close to Hamel about 10 miles east of their aerodrome.

At about 10.45am, Lieutenant Edmond Banks, the Observer in one of the 3 Squadron RE8s, and his pilot, Lieutenant T. L. Simpson, spotted Richthofen’s Circus. Nearby, the other RE8, manned by Garrett & Barrow, saw the same formation. The 3AFC war diary describes that a section of 4 triplanes approached, two stalked Simpson & Banks' RE8 and the other two Garrett & Barrow. However the RE8 'Combat in the Air' and sortie reports both separate the two attacks by five minutes, so there was some degree of circling-around by the triplanes, well above the RE8 altitude, to gain position. Only four triplanes were reported. The visibility was hazy.

The Pilots kept quickly turning their RE8s to favourable positions so their Observers could get clear shots at the attackers, which were swooping from 7,000 feet onto the two RE8s. Some time during the next 6 or 7 minutes, Lieutenant Barrow fired his Lewis gun at point-blank range into one of the attacking enemy triplanes. It went down. However it appears, from research of records, this was another German red-nosed triplane, that of Hans Weiss, not the Red Baron’s aircraft. Also Lieutenant Banks from that day onwards, until his death in 1971, was reported as saying that he'd been the one to shoot down the Red Baron’s famous triplane. (Following this brief interruption, both RE8s continued with their photography missions!)

3 Squadron were to learn that a few minutes after the RE8 dog-fight had finished, the Red Baron's red triplane became engaged in a chase after a Sopwith Camel from 209 Squadron, Royal Flying Corps, based close to 3 Squadron and piloted by an inexperienced newly arrived front-liner, Lieutenant Wilfred May. May had broken away from an encounter between 209 Squadron and the main force of Richthofen's Circus. May's Vickers machine gun had jammed so he was sneaking back to his aerodrome at Bertangles almost at ground level when suddenly the Red Baron appeared behind him firing his twin Spandaus.

It was while May’s evasive tactics were leading them up the Somme Valley at low level, deeper into Allied territory, that May's Flight Commander, Captain A. Roy Brown, saw his fellow Canadian's predicament and zoomed down from 2,000 feet to help him. At top speed, Brown closed on Richthofen, firing into the right side of the red triplane from behind but from slightly above, while Richthofen was still chasing and shooting at the zig-zagging May. Brown’s Camel had too much speed to stay behind Richthofen so he was forced to zoom away from the now tree-level chase as he lost sight of both aircraft behind trees. But he was sure he'd seen his tracer bullets striking the red triplane and, as he later reported, its pilot. But this reported hit obviously didn't stop Richthofen who still continued to pursue and shoot at May for another mile or two until they were over the A.I.F. rear areas near Vaux-sur-Somme.

Many Australian soldiers commenced to independently fire their guns from the ground at the red triplane streaking overhead and still in pursuit of May. Suddenly, the red triplane wobbled, side-banked upwards, swerved left and crashed. Ground fire seemed to have hit home and analysis by historian C . E. W. Bean at the time concluded that the fatal shot had probably come from a 24th Machine-gun Company Vickers fired by Sergeant Cedric Popkin. Either way, the Red Baron was dead.

3 Squadron again entered the scene. The triplane had come down near an abandoned brick-kiln adjacent to the Bray-Corbie road and only about eight miles from the Squadron's aerodrome at Poulainville. The location was under direct observation of the enemy, who had commenced a continuous "box" shelling of the area surrounding the little damaged triplane after they saw Australian soldiers running to the crash site and removing souvenirs. 3rd Squadron was ordered to recover the body of the Red Baron and the triplane and bring both back to the aerodrome.

Crossley Tender.

So a party of 3 Squadron personnel set out for the area, ordered to bring back the body and the aircraft. The party left Poulainville late that Sunday morning in a Crossley Tender and headed for the crash site.

Air Mechanic Colin Collins crawled out under enemy fire and hitched a cable to the Baron's body. Later, after dark, the rest of the party collected the aircraft and the remains were taken back to the aerodrome.

At 11.30 pm that night, a postmortem was carried out in one of the canvas hanger tents. Photographs of the body had already been taken and most of the Baron's personal effects souvenired, before four Medical Officers with 3 Squadron's Commanding Officer, Major David Blake discovered that the Baron had been killed by a single bullet which entered his body at the rear and slightly below the right armpit before passing through his chest and emerging from the left side about 4 inches below the armpit but about 3 inches higher than the entry point - clearly a bullet that must have been fired from a position below the Baron's triplane.

Whilst the Red Baron's aircraft was in 3 Squadron's custody, it was a source of great interest.

...But by the time the official request from army headquarters arrived to turn over the aeroplane to the authorities, there was very little of it left!

As the sun set the next day, the airmen of 3 Squadron formed a Firing Party at Bertangles Cemetery, providing full military honours for the burial of one of the War's greatest and most legendary airmen, whilst the battle for the Somme continued.

Exceptionally dense fog caused the Squadron's pilots and observers frustrations, delays and casualties while carrying out their photographic missions during the rest of April, until, on the 4th of May, the Squadron moved 3 miles north to Villiers Bocage.

From here, contact patrols were carried out regularly, some starting before 4am and flying at low altitude towards the Allied lines, where the observer would sound a Klaxon horn fitted to the RE8 as a signal for the front line of troops to light their flares to indicate their most forward line positions. The positions indicated were marked on a map by the observer and this map with any other relevant written information would be dropped by the RE8 at the Brigade Headquarters. Counter-attack patrols were also regularly carried out to determine the positions of the enemy's front line and positions. While these patrols were taking place, enemy aircraft and ground fire continually attacked the RE8s and the Squadron suffered more casualties.

During May, Squadron losses included one Flight Commander who was killed and two other Flight Commanders who were wounded while in combat with the enemy. But the Squadron also scored some victories. Besides bringing down at least three enemy aircraft in the period from May to early June, a Squadron RE8 forced down an enemy Halberstadt aircraft which landed intact at 3 Squadron's aerodrome.

The Captured German HalberstadtTowards the end of June, the Fourth Army asked 3 Squadron for assistance in dropping quantities of small-arms ammunition by parachute to the machine gunners in the front line. The system then being used required two soldiers to risk their lives carrying one box of a thousand rounds which would keep a machine gun firing for less than five minutes. Each delivery meant travelling two or three miles under enemy fire, so casualties were heavy.

Small parachute for

ammunition-dropping. (Harold Edwards Collection)

At first the RE8 crews tried throwing the boxes of ammunition over the side with little parachutes attached but the parachutes broke and created flying missiles capable of killing the awaiting troops.

So an ingenious airman, Lawrence Wackett [later to become a leading figure in the Australian aviation industry], modified the RE8 bomb racks so that they could carry boxes of ammunition; thus they were able to successfully make these ammunition drops with the required accuracy into the areas of need.

On the 4th of July, twelve aircraft from 9 Squadron, Royal Air Force were attached to 3 Squadron to help them drop 87 boxes of ammunition to machine gunners fighting a critical offensive near Hamel. Fighting was so intense that two aircraft failed to return that day but at least two enemy aircraft were brought down by the RE8s which were carrying out protective and reconnaissance patrols in the Hamel area.

Destroyed village in the

Somme. Every white mark is an artillery-shell scar.

Early in July the Australian Prime Minister, the Right Honourable William Hughes, known to all as "Billy" Hughes, visited the Squadron and showed keen interest in the work they were doing. It was at this time that plans for the Squadron's coming role in the Battle of Amiens were being prepared by the leaders of the Fourth Army.

The Squadron’s task was critical because all forces knew that the conclusion of the War was now a distinct possibility, if the outcome of the pending Battle of Amiens was successful. General Sir Douglas Haig approved a plan to start the offensive on the 8th of August, 1918 by advancing 2nd and 3rd Australian Divisions two miles to a crest of a spur running north-east from Marcelcave to Cerisy. This would allow 4th and 5th Australian Divisions to assemble in the Cerisy Valley so they could leap-frog 2nd and 3rd Divisions and advance a further three miles to a line running from Morcourt, through the north tip of Harbonnieres and then south-east to the Amiens-Chaulnes railway line. Once these objectives had been achieved, the plan called for a further advance by 4th and 5th Divisions for another mile to a new line running from the River Somme near Mericourt through St. Germaine Woods down to the Amiens-Chaulnes railway line south of Harbonnieres.

Map showing the course taken by

Australian Corps in the 8th August, 1918 offensive.

[Source: Australian War Memorial]

3 Squadron's role was destined to follow that of previous campaigns, where they had kept Australian Corps Headquarters supplied with information gleaned by reconnaissance and contact patrols, flew low over the enemy's lines to drown out the noise of Allied tanks advancing, laid smoke screens, directed artillery shoots and called in artillery on German troop concentrations and guns. In preparation for the inevitable RE8 crashes, a break-down squad consisting of fitters and riggers and commanded by Captain Ross, the Equipment Officer, was sent to the forward zone with a Leyland lorry and a Crosley tender and trailer to salvage or repair aircraft forced to crash-land near the Front Line.

At exactly 4.20am on the 8th of August, 1918, the battle commenced. Eight RE8s from A and B Flights had taken off a little after 4.00am in very overcast weather but nevertheless dropped their smoke bombs on the allotted line south-west of Cerisy about 13 miles away just as the ground troops commenced their spirited surprise attack. By 6.20am, the first stage was successfully completed and the Allied Front Line had been advanced according to plan.

During the next nine hours, the Squadron flew contact patrols and counter-attack patrols continuously and became "the eyes" of the progressing army, reporting their observations by dropping marked maps and messages at the Fourth Army Headquarters. Seven air combats were recorded that day with the loss of one RE8 which had been attacked near Mericourt by nine Fokkers. Both the pilot and observer were killed.

Harbonnieres, Somme

Valley, 8 August 1918. The

28cm German railway gun, known as the "Amiens

Gun", on

the day of its capture by AIF troops. The words 'captured' and

partly obscured 'Australia' has been painted on the mounting.

The camouflaged barrel is displayed at the Australian War

Memorial in Canberra ACT. Captain John

Duigan of No.3 Squadron AFC and his observer Lieutenant A. S.

Paterson were the first to locate the gun

during a photographic reconnaissance mission. Attempts

were made by the Allies to destroy this powerful weapon, but to no

avail. During the August 8 advance, the train was bombed by

a British Sopwith Camel,

causing the German soldiers on board to evacuate.

Although RAF aircraft and British cavalry were the first to engage

the gun, it was then quickly claimed by the advancing Australian

infantry, who drove the train back out of the battle zone.

[AWM A00006]

Enemy aircraft in the area were more numerous and more active during the next few days, whilst the Allied ground advance continued at even greater tempo. In spite of constant attacks from air and ground, the RE8s had the responsibility of photographing the whole of the changing Front Line and the enemy territory to a depth of 3 miles, sometimes in unbelievably bad weather. Many photographs had to be developed, printed and distributed to the various Divisional ground units. In fact, it was estimated that 90,000 prints were processed by the Squadron, with the assistance of the Wing's photographic section, during the entire battle.

By mid-August, the Army was preparing for its next offensive advance eastward to Peronne. The need for artillery reconnaissance was urgent, so in a five day period, 3 Squadron's RE8s carried out 27 patrols, each of approximately three hours duration, to pin-point the locations of the enemy's artillery batteries.

On the 22nd of August the Army's push eastward began and the RE8s were used for ammunition drops as well as the usual patrols. The enemy counter-attacked late that day and bitter fighting continued into the next day. RE8s loaded with phosphorus bombs left at 4.45am that morning to lay a smoke screen north of Chuignes and, by late afternoon, they were bombing and shooting enemy ground positions entrenched in the woods north-east of Estrees. In between they carried out the usual contact patrols and counter-attack patrols.

And so this pattern continued until the end of August, by then the ground forces had advanced to the western banks of the River Somme near Peronne having swept the enemy to the eastern side. By now the Squadron's daily patrols were using an advanced landing ground at Glisy for refuelling and re-armament, although a new advanced airfield ten miles further east, near Proyart, was established on the 3rd of September after Perrone and Mont St. Quentin had been captured and nine other major towns had been cleared of enemy positions.

Those early September days involved the Squadron in low-level road and trench strafing to harass the retreating enemy as well as long distance photographic patrols to determine a measure of their now obvious withdrawal towards their own Hindenburg Line.

Early on the 17th of September, a violent thunderstorm tore the Squadron's canvas hangers to shreds and damaged every single aircraft in them. Even though several were seriously damaged and others beyond repair, all officers and airmen worked without stopping to rebuild the RE8s so that, by nightfall, 15 serviceable aircraft were ready for the next day's patrols.

Canvas Hangars 1918

[Painting "AIF Aerodrome Near Bertangles" by Henry Fulwood. AWM ART02477]

Shortly after, a visit by the Australian Corps Commander, Lieutenant-General Sir John Monash, brought official praise to the Squadron for not only their dedication to duty since their arrival in Europe but for the accuracy and promptness of their reconnaissance reporting. And, for the rest of September 1918, duty was both demanding and varied.

The Front itself was changing continuously as the offensive by the Australian forces thrust deeper into enemy-held ground, requiring more and more up-to-date photographs. On the 21st of September, the Squadron commenced a new technique of taking these photographs from the enemy's side at low level so that the result would be a view of the Australian lines from the enemy's view-point.

Later that day the Squadron commenced its move to yet another airfield ... this time five miles south-east to Bouvincourt and only a few days after this, the RE8s commenced night bombing, completing a very successful raid on enemy forces dug into the high ground near Gricourt. Towards the end of September, 27th and 30th American Divisions moved into the area and 3 Squadron flew reconnaissance for them as well as for 3rd and 5th Australian Divisions.

A Bristol F2B Fighter which had been allotted to the Squadron took oblique photographs of the Joncourt-Villers Outreaux line and even though heavy ground fire damaged the fuselage and the radiator, it didn't prevent it returning with valuable information. Attacks from enemy aircraft on the Squadron's RE8s hadn't let up but whenever RE8s were flown by experienced crews and particularly when two RE8s flew together they didn’t seem to have any difficulty holding off four or five attacking enemy scouts and generally being successful in forcing their withdrawal.

On the 29th of September at 5.50am, the storming of the Hindenburg Line began. Ever since the famous Battle of the Somme in March 1916, the enemy had been preparing and fortifying this line as a major defensive position. 3 Squadron was called upon to observe the situation and flew many patrols that day. By now, some RE8s were reporting by wireless telegraphy from the air in addition to the usual system of dropping simplified reports at Army Headquarters and confirming these by written report after landing.

A Smashed Church, Proyart

France.

As the intensity of the battle increased, all Squadron aircraft carried full loads of bombs and extra ammunition so that they could attack any enemy positions they came across after they'd carried out their reconnaissance missions. The ammunition loading into each gun-belt was generally three ordinary bullets, then one tracer followed by one armour-piercer and, on occasions, one Buckingham (or incendiary). (The Pomeroy, which was an explosive bullet, wasn't used by the Squadron. They were so sensitive they had to be wrapped in cotton wool to prevent accidental explosion.) By now, many of the original pilots and observers had either been killed, wounded or sent back to England to 7 Training Squadron to train new airmen; many of whom arrived at the Front posted to 3 Squadron.

The rest of October was busy. The Allies were advancing strongly and 3 Squadron was supporting them, but when the Australian Divisions were withdrawn and sent into reserve at Amiens, their place being taken by 9 Corps, it left 3 Squadron without a Corps to work with. It was therefore assigned to the Fourth Army as a reserve Squadron and began assisting 9 and 35 Squadrons, Royal Air Force, with artillery observation work. It was at about this time that two more Bristol F2B Fighters were added to the Squadron for special long-distance reconnaissance and shortly after that, a full flight of Bristols were attached to the Squadron, with a ground crew made up of Royal Air Force personnel but all pilots and observers being provided by 3 Squadron. This flight was called "O" Flight, RAF.

The Squadron's original Commanding Officer, Major David Blake received a transfer to England on the 26th of October and Major W. H. Anderson was given command of the Squadron now suffering badly from a flu epidemic with over 40 mechanics hospitalised. Nevertheless, patrols were maintained and they observed clear signs that the enemy was preparing to retreat.

3 Squadron RE8s (Harold Edwards

Collection)

The last offensive of the War started on the 4th of November and 3 Squadron provided smoke screens to cover the Allied troops' advance. Carrying phosphorus bombs, the combined flights flew to five different pre-planned positions and, at exactly 5.45 am, an hour before dawn, they dropped their bombs as the artillery open fire. During the rest of the day, many more screens were regularly laid and between 3.30 and 5.00 that afternoon, 14 separate bombing raids were carried out as well.

On the 9th of November, 3 Squadron patrols reported the sighting of white flags fluttering from prominent buildings in the Cerfontaine-Silenneux vicinity and numerous columns of enemy vehicles and troops, some holding and displaying hostage civilians to assure they wouldn’t be attacked as they retreated.

On the 10th of November, a 3 Squadron RE8 took part in the Squadron's final combat with the enemy. Ten Fokkers attacked this RE8 over Sivry but a formation of fighters from a nearby Squadron drove them off without injury to the aircraft. At 11.00 am the following day, an Armistice was declared and all hostilities ceased.

Thus ended the first glorious era in the life of 3 Squadron. From the time of its formation slightly over two years beforehand, it had acquitted itself admirably from any point of view for it had carried out almost 10,000 hours of war flying from 10 different aerodromes, and in the course of this flying observed and reported upon 735 artillery exchanges, dropped over 6,000 bombs, fired at least half-a-million rounds against enemy targets and exposed over 6,000 photographic plates covering some 1,200 square miles of enemy territory.

During its War Service, 88 pilots and 78 observers were attached to the Squadron of whom 11 pilots and 13 observers were killed in action and another 12 pilots and 12 observers were wounded and hospitalised. The Squadron lost 11 RE8s over enemy lines but succeeded in bringing down 51 enemy aircraft. The Decorations won by the Squadron's personnel during this War period were:

1 Order of the British Empire

3 Military Crosses

16 Distinguished Flying Crosses

5 Meritorious Service Medals

7 Mentions in Dispatches

3 Foreign Decorations

Besides the men who flew in the aircraft and who generally held the rank of Lieutenant (unless they were Flight Commanders with the rank of Captain or the Squadron Commander whose held the rank of Major) the Squadron's records show that three Recording Officers, three Equipment Officers, four Wireless Officers, three Armament Officers and 15 attached Allied officers were involved with the duties of the Squadron during the war years.

But the Squadron could not have achieved its objectives without the men who made the Squadron work ... the four Warrant Officers, the eight Flight Sergeants, the 27 Sergeants, the 32 Corporals, the 67 First Class Air Mechanics, the 202 Second Class Air Mechanics, the five Third Class Air Mechanics and the 51 Privates and 94 other Army ranks who, at some stage, worked with the Squadron during its war service period. They were the ones who, for pay of only a few shillings a day, worked consistently long hours; usually in poor living conditions. Food wasn’t always plentiful and they sometimes used Army issued biscuits (called "shrapnel" biscuits) as fuel - since the biscuits were so hard that they were more combustible than they were palatable!

Officers on flying duties earned 5 shillings a day (50 cents) flying allowance over and above the 7 shillings and 6 pence per day wage paid to a 2nd Lieutenant or the 10 shillings and 6 pence a day paid to a full 2 pip Lieutenant. Like the ground crew, they endured much the same uncertain living conditions but, as well, they had to contend with the dangers of flying against an enemy who threw aircraft, ground fire and "archie" or ack-ack at them almost every time they flew.

They were often required to attack balloons which the enemy employed to carry out artillery observation. These balloons usually floated at about 3,000 to 4,000 feet and were anchored in heavily-defended areas. As a target they were quite vulnerable to incendiary bullets, so they were pulled down by their windlasses as soon as an Allied aircraft approached. Often their observers would parachute from their basket while the attacking aircraft was running the gauntlet of fierce anti-aircraft fire. While the Squadron wasn't credited with destroying any balloons, many were attacked by 3 Squadron pilots with at least satisfactory results.

But poor living conditions and a strong enemy weren't the only problems 3 Squadron had to overcome during the war.

In the early months, they had to do their part in helping the Royal Flying Corps and the Australian Flying Corps Command convince a partially skeptical Army ground force that aerial photography gave information that was not only useful but often invaluable.

In early years, some of the Army Command held the viewpoint that aeroplanes were a novelty which would soon disappear and the photographs they took would "only be useful as souvenirs."

Fortunately, the R.F.C and the A.F.C. succeeded in proving the worth of the aeroplane and its capabilities. In the latter years of the war, Army Commanders treated combat not so much a contest of brute force, but as a science of analysis, fed by intelligence information provided especially by the Allied Air Forces, which by then had become respected, and even envied, by many of the fighting troops on the ground.

An average AFC man serving

with 3 Squadron.

2nd Air Mechanic (2AM) Harold

Edwards was an instrument fitter who engraved the plaque

for the Red Baron's coffin.

Before Harold's death in 1998, he became famous as the last

living veteran of the WW1 Australian Flying Corps.