The Battle of Amiens, 8th August 1918.

![]()

[Extract from Fire in the Sky by Michael MOLKENTIN.]

...As far as the British Fourth Army's commander, General Henry Rawlinson, was concerned, the [previous] Allied victory in the Battle of Hamel [on July 4, 1918 - in which 3 Squadron AFC played a major part] was irrefutable proof that the German army’s morale and defensive capabilities were deteriorating rapidly. Moreover, it was evidence that Rawlinson’s army now had the resources and tactics to shatter the enemy's front and force them back to their pre-Spring Offensive line. On the very day after Hamel, Rawlinson secured permission from General Headquarters to draft plans for another offensive in the Somme sector along the lines of the Hamel plan. This would be a substantially bigger affair, though.

After a series of revisions involving political wrangling between the British, French and supreme allied high commands, Rawlinson's scheme turned out to be a coalition effort, involving the British Fourth and French First Armies along a 30 kilometre front, extending from the Ancre, across the Somme and south to Moreuil. The British Empire forces would advance in the north, parallel to the Somme, with three corps in the line: the Australian Corps between the Somme River and the Villers-Chaulnes railway; the British III Corps to their north (on the other side of the Somme river); and the Canadian Corps immediately to their south.

Rawlinson's objectives were ambitious: a single-day advance of 11 kilometres in three stages. In the Australian sector, the 3rd and 2nd Divisions would advance side by side, 3.5 kilometres to the 'Green Line'. They would pause for two hours and dig in, while the field artillery moved forward to get in range of the next objective. Fresh troops (the 4th and 5th Divisions) would then 'leap frog' through the first wave and advance 5.5 kilometres to the second objective - the 'Red Line'. If enemy resistance broke down completely, these troops would then push forward another 1,800 metres to occupy the 'Blue Line’ - the day's ultimate objective.

Map showing the course taken by

Australian Corps in the 8th August, 1918 offensive.

[Source: Australian War Memorial]

Rawlinson's plan for what became known as the Battle of Amiens was based explicitly on the Hamel plan. To surprise the enemy, there would be neither pre-registration of artillery on to enemy targets, nor a preliminary bombardment. Fourth Army's 2,070 guns would remain silent until 'zero hour'. The infantry would, as at Hamel, be preceded by tanks (537 of them) and would have ample air support. The RAF and Aeronautique Militaire had an overwhelming superiority in numbers on the Amiens front – 1,904 aircraft to oppose the German Air Service's 365 machines. On 29 July, as the multitudes of men, machines and materiel quietly deployed behind the battlefront, Rawlinson's headquarters finalised the scheme and set 'zero hour' for 4.20 a.m. on 8 August.

In the fortnight prior to the offensive, No.3 Squadron shouldered a heavy workload to help the Australian Corps prepare for battle. First, there was a concern with secrecy. Special flights patrolled continuously by day over the whole Australian Corps area in order to detect and report any activity which might disclose to the enemy our preparation for the attack. Then there were artillery patrols (255 of them in July) to identify the location of as many enemy guns as possible prior to the attack. By the eve of the battle, the British gunners knew the precise location of 504 of the 530 enemy guns facing them. Finally, there were photography patrols. The squadron photographed the Australian Corps front and, with the wing's photographic section, produced 90,000 prints. These were overlaid with topographic lines and each Australian infantry platoon received one, depicting the section of terrain they were required to advance across. It is no wonder Air Mechanic Frank Rawlinson recalled seeing his pilot 'off with the first rays of daylight and back after the setting sun, for a good while' prior to the Battle of Amiens.

On the afternoon of 7 August, Major Blake [3 Squadron's Commanding Officer] briefed the airmen on the plans for the following day. ‘A’ Flight was responsible for artillery observation and B Flight for counter-attack patrols. Both would also drop smoke along the south bank of the Somme to protect the Australians’ left flank from German guns on the high ground across the river. C Flight would do the contact patrols. Using klaxon horns fitted to their RE8s, the pilots would signal the infantry to light flares and then drop reports of their progress to corps headquarters. In this, the airmen of C Flight would play a critical role in the direction of the battle. If the infantry advanced as far as Rawlinson planned, they would be well beyond the range of telephone cables for several days.

A heavy mist blanketed the battlefield at dawn on 8 August 1918. Fourth Army's 2,070 guns thundered to life at 4.20 a.m., shaking the earth and lighting up the sky. A British bomber pilot was above the sea of grey mist when it began:

The landscape was a mass of flame, the stabs of fire from the guns and shells only lighting up a haze of smoke. It was an inspiring sight and many were the shells that swept unseen past our planes. The greatest day of the war in the air had begun.

Eight No.3 Squadron crews took off on smoke-dropping sorties between 4.00 a.m. and 6.00 a.m., but ironically couldn’t even find their targets because of the mist already covering the landscape. Half the crews couldn't find their way back to the aerodrome and landed around the countryside.

'One of ours flew nearly to the coast, before he could get out of it,' recalled Frank Rawlinson. 'They were down on roads and on cottages, and one chap who had spotted our Verey lights made a marvellous landing.'

In spite of the fog, the rest of the RAF got on with its job too. Rawlinson and his fellow mechanics were heartened to count 400 British aircraft passing over their aerodrome on their way to the battlefield that morning.

The sun started burning the mist off at 9.00 a.m. and half an hour later 3AFC pilot James Smith [webmaster Neil Smith’s dad] and Oscar Witcomb took off on a Contact Patrol to check on 4th Division's progress on the left. Their report was promising. The first objective was secure, and the Australian infantry and tanks were well on their way to the second objective. ‘Apparently not much opposition’, they recorded; ‘very little shelling’ and the enemy in front of the advancing Australian line was limited to isolated groups. The German defenders, it appeared, had been completely overwhelmed by the artillery barrage and rapid advance. Smith saw a group of 200 enemy prisoners and 'several groups of 50' heading west in the wake of the advancing Australians. He dropped copies of his report at divisional, corps and then army headquarters before landing.

A British tank moves forward while German prisoners bring

back stretcher cases.

Meanwhile, Lock and Barrett were on their way to see how the 5th Division was getting along, on the right side of the advance:

We got nearly to the place the infantry were thought to have reached when one of our magnetos failed, and the engine did not have sufficient power to fly us home. We had to land in a field, just near Villers-Bretonneux, and although it looked all right from the air, we found it was full of shell holes, one of which we struck when we landed. The machine hopelessly crashed, but my pilot and I got off with a few bruises, although my right arm is still sore owing to the knock it got.

A mobile 'breakdown gang' of squadron mechanics was on the scene shortly afterwards to retrieve Lock, Barrett and the bits and pieces of their RE8.

The next contact patrols went up an hour later, and just before 11.00 a.m. reported Australian troops digging in along their second objective. They faced 'not much opposition' and 'only light shelling' from the enemy, suggesting the advance would continue to the final objective.

As the morning wore on, enemy Jastas [fighter squadrons] arrived from neighbouring sectors and made their presence felt. Hugh Foale and Frank Sewell, both ex-infantry and both 20 years old, successfully identified the 5th Division digging in on its final objective at noon. Just as they were about to leave and drop their reports at divisional headquarters, Foale spotted a pair of Fokker DVIIs [Germany’s best fighter aircraft] strafing the diggers. Perhaps because of an affinity he felt with his old comrades, he turned the lumbering RE8 around and circled above them. Sewell opened fire with his Lewis gun and 'one enemy aircraft dived steeply and burst into flames'.

The other noon contact patrol crew, Edward Bice and John Chapman, were further north, checking on 4th Division's progress, when nine Fokker biplanes bounced them. Later in the day, advancing Australian troops found their bodies beside their wrecked RE8. A chaplain buried them on the battlefield, and fortunately (and this wasn't always the case) recorded the location.

After the war, exhumation units moved them into Heath Cemetery at Harbonnieres. Apparently, their remains couldn't be distinguished, as today they lie together in the same plot. Bice's death was especially tragic, and not just because he was an only son. He had enlisted in the infantry in early 1915 and survived a string of military blunders at Gallipoli, Pozieres and Bullecourt, only to die on his nation's most triumphant day in the war. Bice had also recently married a girl in London. She was five and a half months pregnant with his daughter when he was killed.

Heath Cemetery, where 3AFC’s Bice and Chapman rest with

983 other Aussies, mostly killed in August 1918 (110 of them on

the 8th).

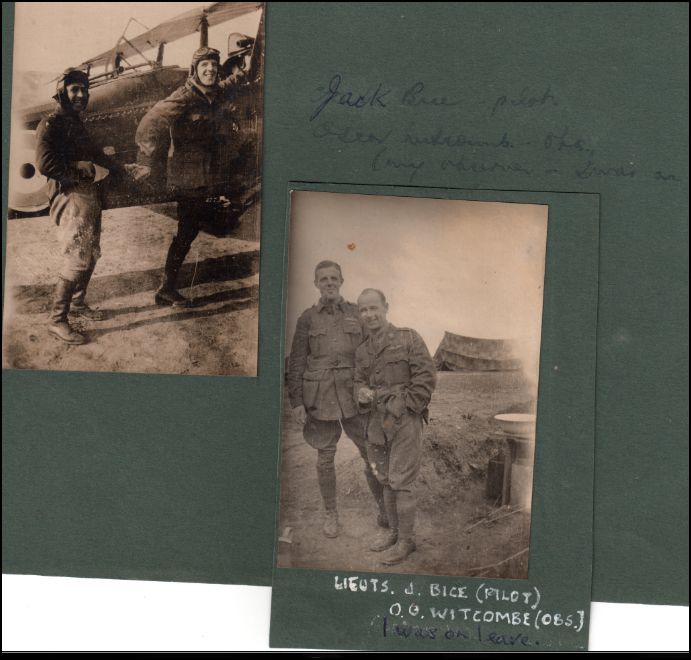

[Left:] Portraits of Jack

Bice (the taller man in both photos) in France, from Lee Smith's album and [Right:] Jack's gravestone.

When Bice and Chapman failed to return, another C Flight crew set out to determine 4th Division's progress. They flew over the battlefield at 200 feet and used their klaxon to call for flares. A line of them, along with waved hankies and flashed tin plates, indicated that the majority of the 4th Division was digging in on its final objective too. During the afternoon, another crew photographed the Australian Corps' new front line, 11 kilometres beyond where it had been that morning and with little enemy opposition before it. The Canadians had likewise secured all of their objectives, although north of the Somme, III Corps had a tough time and had not kept up with the Australians south of the river.

A and B Flights worked hard throughout the day but found their services of limited value. The Australian infantry had surprised the German artillery lines in the dawn mist, capturing 173 guns. There were few targets, therefore, for A Flight to direct fire onto. Likewise, B Flight didn't see any counter-attacks develop, so instead dropped their bombs on retreating troops and motor transport.

3AFC Observer Tom Prince looked down over the tidal wave of men and machinery that the Germans faced at Amiens on 8 August 1918. Reflecting on it in 1970, Prince considered the battle to be 'the end of an era'. It 'marked a stage in the transition from the pace of a man and a horse to the swifter progress of mechanised war'.

The German commander Erich Ludendorff famously wrote in his memoirs that 8 August 1918 was 'a Black Day for the German Army in the history of the war’.

Likewise, the official German history of the battle (Die Katastrophe des 8 August 1918) acknowledged ruefully that:

The heaviest defeat suffered by the German Army since the beginning of the war had become an accomplished fact.

What was perhaps most disturbing to German commentators was the number of their soldiers who surrendered readily. 'Men had sought safety in flight,' is how the German official historian summed it up, an interpretation the Allied statistics certainly support. Fourth Army and the French First Army had taken about 18,500 prisoners during the day and, according to German sources, had killed or seriously wounded another 9,000. The advance had cost Fourth Army, by comparison, fewer than 9,000 casualties in total.

![]()

Extract from Fire in the Sky by Michael Molkentin. Pages 284-290.